Kentridge says that he led ‘two lives as an artist’. First, after university where he completed his BA in Politics and African Studies and studied Art at the Johannesburg Art Foundation. He made etchings and taught in an art school but then he decided he didn’t have a right to become an artist as he had nothing to say. He tried to become an actor, failed at that. Tried to become a filmmaker, failed at that. But he discovered, almost in spite of himself, that he was back in the studio making charcoal drawings.

For William Kentridge, escaping his true identity only resulted in failures which needed to fail in order for him to realize that they served as an opportunity of something larger. He incorporated into his drawings, gestures and movements, filmmaking techniques, performance and acting, stage direction from his “failures” and in the end he was reduced to being an Artist. With help from Clement Greenberg and the roles of justice his parents played during the apartheid, Kentridge realized that a political situation such as South Africa’s demanded political art.

His films are set in the over-exploited, scorched , industrial and mining landscape around Johannesburg, his home and muse, which represents a legacy of a time of abuse and injustice.

Kentridge’s work is often considered ‘political’ and ‘polemical’. Its central livelihood is making the audience aware of constructing meaning rather than receiving information. No doubt this can be partially attributed to the time, space and context surrounding the works’ creation- its driven by what he has seen and the evolution South Africa has been through. In his own South African context, this era is understood as the beginning of the end.

Kentridge’s work and the connection to the people, the politics and the world is fundamental to him even if the work isn’t about that, even if its painting a landscape or drawing a landscape or an ink drawing of a portrait, it’s very inflected by what it is to be there by the city of Johannesburg that is an animation in itself. In his attempts to codify the place of politics in his work Kentridge says he likes the example set by Manet, “who did very political work but also painted a lot of flowers”. He never felt that he needs to distinguish strongly between the works as it all flows into the studio and different parts get picked up at different moments.

Challenging the paradigm of being just an artist, he would use different mediums ranging from charcoal to operas to demonstrate the nuts and bolts of an idea. Yet, we see, the weight of local history flooding Kentridges work and the dialogues with international modernism. Thus, as Kentridge best puts it, “In the end all work I do is about Johannesburg.”

This is an extract from the my Chosen Practitioner Essay and it truly changed how I think about my identity and my country. In both my figurative works before joining the college, the works I recreated were inspired by India and yet again in the end, Kentridge’s landscapes and his dedication to the history of Africa and his usage of metaphors, allegories and symbolism to treat apartheids trauma, sparked the love for my country and its rich history which has shaped me into who I am today.

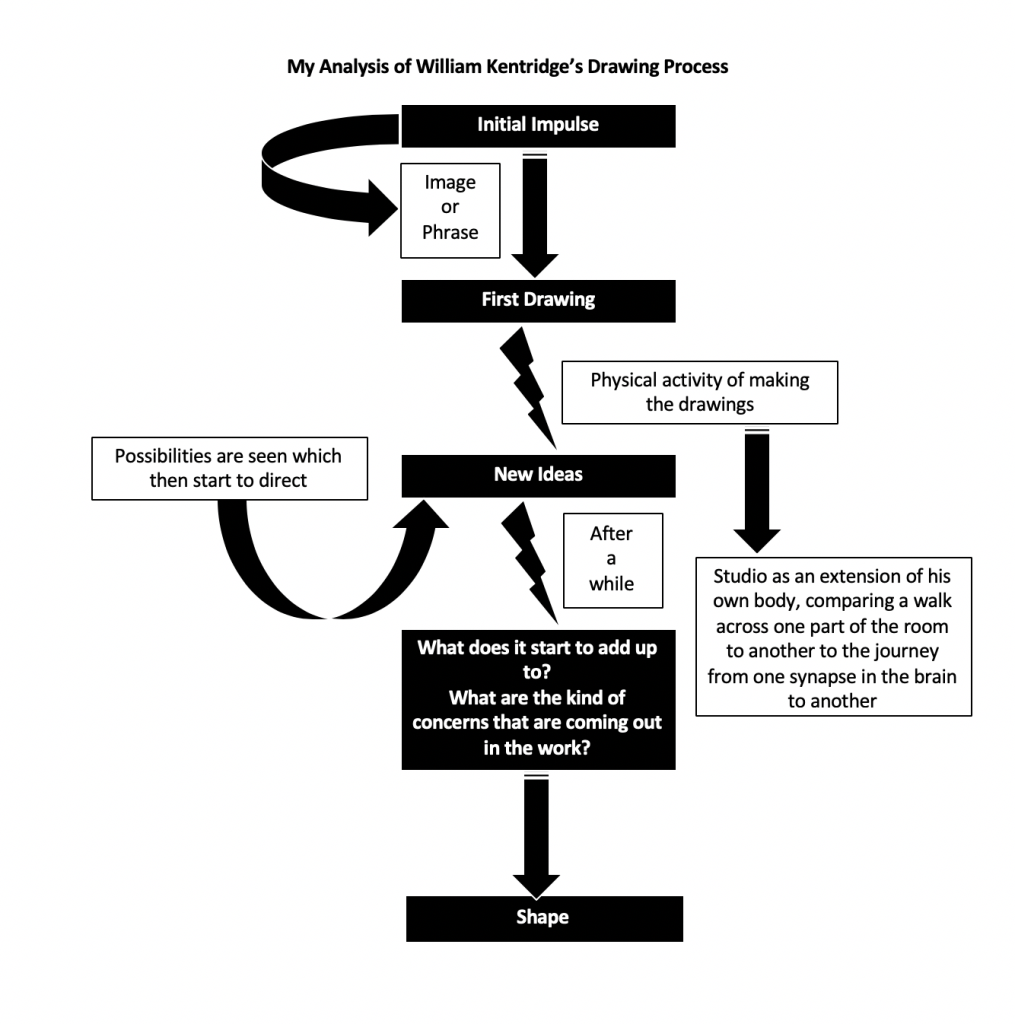

His usage of charcoal and the interdisciplinary nature of his work to display the nuts and bolts of an idea was inspiring and I began to integrate his processes and mediums into my work.